Where are the memories? Exploring Black Community Archives

by Chaitra Powell

October is officially National Archives Month. Many libraries and archives will be launching social media campaigns and sponsoring programs that highlight their special collections and encourage people to learn more about why archives are so important. The archival landscape reflects societal power dynamics by showcasing whose history is protected and whose history is lost. Archives can exist in many formats including papers, recordings, photographs, art forms, artifacts, and more. These materials can live in museums, homes, universities, churches, community centers – basically anywhere a community deems is appropriate. The diversity of formats and locations of archives is important to outline because some archives live outside the perimeter of mainstream institutions because of multi-generational systems of structural discrimination and exclusion. This legacy requires contemporary archives practitioners to think beyond the traditional tenants of the profession and find creative and generous ways to engage with marginalized populations. What follows is a short narrative describing how the Southern Historical Collection approached this work with one set of our impressive community partners.

An extraordinary confluence of UNC professors, humanities scholars, and engaged mayors from these towns brought the Historically Black Towns and Settlements Alliance (HBTSA) to my attention in 2014. HBTSA was originally composed of five towns, Eatonville, FL, Mound Bayou, MS, Hobson City, AL, Tuskegee, AL, and Grambling, LA — they have since grown to include more towns in more states.

It was clear from the beginning these towns did not represent traditional collection donors – they wanted to hear more about how the archives could serve their interests. Their primary one being support for using their impressive histories to promote cultural tourism in the towns. Representatives shared stories about how they could not register as historic landmarks because the necessary proof was last seen in someone’s shed – necessitating the need for a centralized archive. They wanted to have the genealogies of their founders properly documented and preserved. They wanted to honor the folks who had lived and died in their communities by cleaning up local cemeteries and clearly documenting the occupants.

Photo of cemetery, featuring an angel figure, flowers and the headstone Bernice Flowers; born: March 20, 1935, died September 31, 1973 in Grambling, Louisiana (2014), taken by Biff Hollingsworth

Photo of archival materials from the home of former Hobson City, Alabama mayor, Mrs. Willie Maude Snow – brought in to city hall to show the extent of dispersed collections (2014), taken by Chaitra Powell

Photo of an unprocessed archival collection in the Tuskegee History Museum in Tuskegee, Alabama (2014), taken by Chaitra Powell

Photo of an Eatonville baseball or cricket team, n.d. shared by Maye St. Julian in her home in Eatonville, Florida (2014), taken by Bryan Giemza

Photo of Chaitra addressing the audience about the Southern Historical Collection’s commitment to the Historic Black Towns and Settlements Alliance (HBTSA) during the conference in Chapel Hill (2015), taken by Jay Mangum

Lastly, they wanted opportunities to share stories in order to engage and inspire the community’s younger generation in the histories of their towns. In order to gain as much context as possible – we made visits to the towns, established working relationships with town stakeholders, conducted archival content surveys, supervised field scholars, participated in weekly HBTSA conference calls, and helped to orchestrate an HBTSA conference in Chapel Hill in the spring of 2015. All of this preparation culminated in three exciting pilot initiatives in Mound Bayou, Mississippi in the Fall of 2015.

1. Document Rescue: The Administration Building of the Knights and Daughters of Tabor of organization held important documents in less than ideal environmental conditions. The building had been ravaged by storms and neglect, leaving it water damaged, dirty, and full of pests. The rooms within the building contained publications, insurance forms, photographs, and ceremonial artifacts that told the story of a Southern based, black fraternal organization. The Southern Historical Collection offered to rent a storage unit in nearby Cleveland, MS for three years and temporarily store the materials until an adequate permanent solution could be found. We worked with the community to move the materials into storage in October 2015.

Photo of a van filled with moving boxes during the document rescue event at the Knights and Daughters of Tabor Administration Building in Mound Bayou, Mississippi (2015), taken by Chaitra Powell

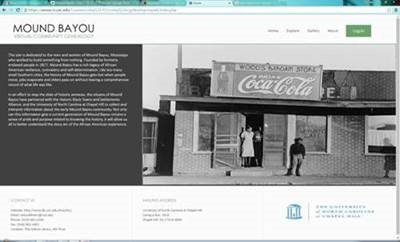

2. Virtual Community Genealogy: In recent years, Mound Bayou has been the site of several field experiences for Duke and UNC graduate and undergraduate students. In the summer of 2015, students worked to compile biographical information on the town’s founders and early residents, up until the middle of the 20th century. They conducted interviews, visited local archives, perused obituaries in home collections in order to build a spreadsheet. In the fall semester, we were able to work with computer science students to turn this spreadsheet into an interactive and searchable website documenting the people, places, and organizations of early Mound Bayou.

Screenshot of the cover page for the Mound Bayou Virtual Community Genealogy (2015), taken by Chaitra Powell

3. High School Student Outreach: One of our community liaisons, a former librarian, and I connected with the principal of John F. Kennedy High School, and organized an after school event in the library to discuss local history. Six students participated in several activities, one included creating an account for the Virtual Community Genealogy website, and entering biographical content found in primary source material borrowed from community members.

Photo of Chaitra with the JFK High School students during the after school local history program in Mound Bayou, Mississippi (2015), taken by Ms. Edna Smith

And in conclusion..

After we finished all of these exciting outreach initiatives we took a serious victory lap! I cited these examples in presentations, conversations, interviews, and short videos for our fundraising campaigns and felt pretty good about the ability of an institution to participate in altruistic and meaningful collaboration with a marginalized community. Our team was feeling so good about it that we crafted a successful grant application to the Mellon Foundation to elaborate on this model of developing community partnerships. HBTSA, along with three other pilot communities are the site of development for a wide variety of tools and strategies to nurture the relationship between the community and the archive.

From this short synopsis, it is clear that sustainability, replicability, costs, personnel, scale, parity across communities, institutional priorities, and many other considerations are necessary to develop a toolkit that has the potential to work with other communities and institutions around the world. So, we are currently using Mellon funding to hire a team of archivists, documentarians, and communication specialists that will unpack what we’ve done thus far, develop techniques to do it better, and determine if our work is having the positive impact that we have been shooting for since the beginning – informed communities who feel empowered to challenge the status quo.